Estimated Reading Time: 11 minutes, 48s.

When you send an email to Tim Pychyl, a procrastination researcher at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, you don’t have to wait long for a response.

Pychyl has been researching and writing about procrastination for more than 20 years, and it shows–he’s one prolific guy. He records the iProcrastinate Podcast, which frequently ranks among the most downloaded on iTunes; writes a blog named Don’t Delay for Procrastination Today (which has a very nice ring to it); and is the author of Solving the Procrastination Puzzle, a concise guide on how to beat procrastination.

Tim Pychyl

I recently interviewed Tim about why we procrastinate, and about what tactics we can use to beat procrastination. What follows is everything I learned.

Why you procrastinate

Before diving into some tactics to stop procrastinating, you should know why you procrastinate in the first place.

According to Pychyl, procrastination is fundamentally a visceral, emotional reaction to what you have to do.

When you put pressure on yourself to accomplish certain tasks, according to Pychyl you “have this strong reaction to the task at hand, and so the story of procrastination begins there with what psychologists call task aversiveness”. The more aversive a task is to you, the more you’ll resist it, and the more likely you are to procrastinate.

Pychyl, in his research and during our interview, identified a number of task characteristics that make you more likely to procrastinate. Tasks that are aversive tend to:

- Be boring

- Be frustrating

- Be difficult

- Lack personal meaning and intrinsic rewards

- Be ambiguous (you don’t know how to do it)

- Be unstructured

The more negative emotions you show toward a certain task, the more likely you are to procrastinate, and according to Pychyl, “any of these [characteristics] can do it”.1

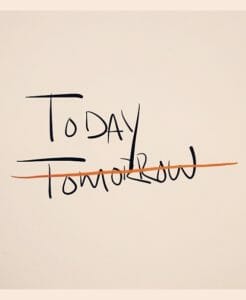

As Tim wrote in Solving the Procrastination Puzzle, “[t]he key issue is that for chronic procrastinators, short-term mood repair takes precedence. Chronic procrastinators want to eliminate the negative mood or emotions now, so they give in to feel good. They give in to the impulse to put off the task until another time.” Then, “not faced with the task, they feel better.”

10 tactics that will help you stop procrastinating

Alas, if there were a magical cure to stop procrastinating, Tim probably would have found it during his more than 20 years of research. But even though there is no magical cure, there are numerous tactics that you can use to quit procrastinating and get more done. I’ve taken my 10 favorite tactics that Tim talked in his book and during my interview with him, and they’re below!

1. Flip a task’s characteristics to make it less aversive

Tasks that are aversive are usually a combination of boring, frustrating, difficult, meaningless, ambiguous, and unstructured. But by breaking down exactly which of these attributes an aversive task has, you can take those qualities and turn them around to make the task more appealing to you.

Tim gave the example of a task that is boring and frustrating. “You’re able to look at it and assess it and say, ‘Oh, this is so boring and I find it so frustrating’, so you make a little game out of it. How can you make it interesting? So I might play a game of, ‘How many of these could I get done in 20 minutes?’. And you find something to do–some competition within it, and so all of a sudden you make it interesting”, and much less boring and frustrating in the process.

Similarly, by making tasks less difficult, meaningless, ambiguous, and unstructured, you can mold what you have to do to be more desirable to you. When you notice yourself procrastinating, use your procrastination as a trigger to examine a task’s characteristics and think about what you should change.

2. Know the ways your brain responds to “cognitive dissonance”

Whenever you realize that you should be doing something but that you aren’t (psychologists call this separation between your actions and beliefs cognitive dissonance), you can respond in one of several ways to feel better about yourself. In his book, Pychyl identifies a number of unproductive responses people have when they procrastinate:

- Distracting yourself, and thinking about other things

- Forgetting what you have to do, either actively or passively (usually for unimportant tasks)

- Downplaying the importance of what you have to do

- Giving yourself affirmations, focusing on other your values and qualities that will solidify your sense of self

- Denying responsibility to distance yourself from what you have to do

- Seeking out new information that supports your procrastination (e.g. when you tell yourself you need to have more information before you get started on something)

Of course, the best possible response to cognitive dissonance is to change your behaviour and get started on whatever you’re procrastinating on, but that’s often much easier said than done.

To push back against these biases, recognizing them is key. Then, Tim recommends that you “list the things that you commonly say or do to justify your procrastination”, and use these biases as triggers that you should respond to your behaviour differently.

3. Limit how much time you spend on something

One of my favorite tactics that Tim recommended is to limit how much time you spend on something. He spoke about his German colleague who limits how much time he allows academic procrastinators spend on an assignment. “He will limit the time they can work on an assignment. ‘Okay, we’re working today and you’ve got twenty minutes to work on that assignment, and you may not work any more.’ And so they go: ‘I’ve got twenty minutes. I better make the best use of it.’” And they do.

Limiting how much time you spend on a task makes the task more fun, more structured, and less frustrating and difficult because you’ll always be able to see an end in sight.

There are some huge productivity benefits to the idea as well. When you limit how much time you spend on something instead of throwing more time at the problem, you force yourself to exert more energy over less time to get it done, which will make you a lot more productive.

4. Be kind to yourself

According to Tim, when you procrastinate “negative self-talk comes out in spades”, which is completely counterproductive.

When I interviewed David Allen, who wrote the terrific time-management book Getting Things Done, one stat he mentioned still sticks out in my mind: that 80% of the thoughts you say to yourself in your head are negative. And it’s pretty difficult to procrastinate without deceiving yourself.

The reason you deceive yourself when you procrastinate is simple: at the same time that you know you should be doing something, a different part of you is very much aware that you’re not actually doing it, so you make up a story about why you’re not getting that thing done. (This is the cognitive dissonance I mentioned in tactic #2.) Be mindful of how kind you are to yourself, and watch out for times when you try to deceive yourself.

5. Just get started

People, as a rule, overestimate how much motivation they need to do something. After all, usually you just need enough motivation to get started. For example:

- To work out, you don’t need to be motivated for an entire hour to finish a workout; you just need to be motivated for the 10 minutes it takes you to pack up and drive to the gym. Once you’re at the gym, you’ll always work out.

- To clean out your basement, you don’t need to be motivated for the entire afternoon; you just need to be motivated for the five minutes it takes you to transition from what you’re doing now to getting started.

- To go for a swim in a cold pool, you don’t need to be motivated for your entire swim; you just need to be motivated for the 30 seconds it takes you to jump in and start swimming.

One of the biggest recommendations Tim had was to simply get started. “Once we start a task, it is rarely as bad as we think.” In fact, once you get started on something, your “attributions of the task change”, and what you think about yourself changes, too.

6. List the costs of procrastinating

The costs of procrastinating can be enormous; as Tim put it in his book, “[w]hen we procrastinate on our goals, we are basically putting off our lives.” Since procrastination is very much an emotional reaction to what you have to do, activating the rational part of your brain to identify the costs of procrastinating is a great strategy to get unstuck.

In his book, Tim recommends that you make a list of the tasks you’re procrastinating on, and then “[n]ext to each of these tasks or goals, note how your procrastination has affected you in terms of things such as your happiness, stress, health, finances, relationships, and so on. You may even want to discuss this with a confidante or a significant other in your life who knows you well.” At the end of the day, “you may be surprised by what they may have to say about the costs of procrastination in your life.”

7. Become better friends with future-you

According to Pychyl, we’re “not very good at predicting how we will feel in the future. We are overly optimistic, and our optimism comes crashing down when tomorrow comes. When our mood sours, we end up giving in to feel good. We procrastinate.”

Research has shown that we have the tendency to treat our future-selves like a complete stranger, and according to Pychyl, that’s why we “give future-self the same kind of load that we’d give a stranger”. (This is also the reason you have 10 food documentaries in your Netflix queue.)

The solution to this? Become better friends with future-you. Here are a few of my favorite ways:

- Create a future memory. Interestingly, research has shown that all it takes to delay gratification is to imagine your future. This is easy to do–for example, if you’re debating between writing a work report today or next week, create a future memory by imagining all you will be able to get done next week if you start the report now.2

- Imagine your future self. Research has shown that all it takes to increase your future-self continuity is to imagine yourself in the future. The more vivid the future feels, the better.3

- Send an email to your future self. Seriously, do it. FutureMe.org lets you send an email to yourself in the future at a date you specify. A great way to bridge the gap between your present and future selves is to tell your future self how your current actions will make your future self better.

8. Disconnect from the Internet when you have to get something done

Interestingly, even though his book has only ten chapters, Pychyl dedicates an entire chapter to the importance of disconnecting from the Internet when you have something important to do. In fact, one of Pychyl’s studies found that 47% of people’s time online is spent procrastinating, which Pychyl calls a “conservative estimate” since that study was conducted before social networks like Facebook and Twitter became popular. “There is little doubt that our best tools for productivity–computer technologies–are potentially also one of our greatest time wasters.”

“To stay really connected to our goal pursuit, we need to disconnect from potential distractions like social-networking tools. This means that we should not have Facebook, Twitter, email, or whatever your favorite suite of tools is running in the background on your computer or smartphone while you are working. Shut them off.”

That might sound harsh, but according to Tim, “if you are committed to reducing your procrastination, this is something you really need to do.”

9. Form “implementation intentions”

Tasks that aren’t clearly defined are ambiguous and often unstructured, which makes you a lot more likely to procrastinate with them. The cure? Form implementation intentions for those tasks.

That’s basically just a fancy way of saying that you should make your tasks more concrete, by thinking about when, where, and how you’re going to do them. Tim is a big fan of implementation intentions. “I have to make sure that I’m not lying to myself right off the top with making a broad goal intention. ‘Yeah, I’ll do that writing on the weekend.’ Well, both the timeframe and the task are defined too broadly to be meaningful at all.

“So, one of the very first things is start making a more concrete and start tying it to something in the environment. And so, these are called implementation intentions. Move from broad goal intentions to specific implementation intentions. So that’s a cognitive technique, where you’re going to do some thinking around: “What am I going to do when?” And that pre-decision is really important.”

10. Use procrastination as a sign you should seek out more meaningful work

You procrastinate a lot less with meaningful tasks that are intrinsically rewarding. For that reason, Tim recommends reexamining your work if you find yourself constantly procrastinating with what you have to do.

“Sometimes I would say procrastination is just a symptom that your life just doesn’t match what you’re interested in and you’re putting everything off because all of your goals are kind of falsely internalized and you’ve got no intrinsic motivation in any of this, and so maybe you should do something else.”

In every job there are going to tasks you find aversive, but when you constantly find yourself procrastinating because your work is aversive, there may be other jobs that are more aligned to your passions, that you will be much more motivated and productive in.

Interestingly, Pychyl’s earlier research shows that depending on the stage of a project you’re in, the effects of these characteristics differ. For example, lack of autonomy will impact how aversive a task is to you a lot more during the “action” phase of a project compared to the “inception” phase of a project. But as a general rule, the more of these characteristics a task has, the more aversive it will be to you. ↩

Source: The Willpower Instinct. ↩

Source: The Willpower Instinct. ↩